Unit 1 - Dysphagia

| Site: | IDEC TrainingCentre elearning |

| Course: | MODULE 1: METHODOLOGY AND TOOLS DEVELOPMENT FOR ADULT EDUCATORS |

| Book: | Unit 1 - Dysphagia |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 7 February 2026, 12:28 PM |

Table of contents

- Lesson 1.1 Dysphagia

- 1.1.1 Swallowing

- 1.1.2 Dysphagia

- 1.1.3. Prevalence

- 1.1.4. Health consequences - Security Complication: Choke, Obstruction, Respiratory Infections, including Aspiration Pneumonia

- 1.1.4.1 Respiratory Infections: Including Aspiration Pneumonia

- 1.1.4.2 Obstruction

- 1.1.4.3 Choking

- 1.1.5. Health consequences - Efficacy Complications: Malnutrition, Dehydration, Decrease Quality of Life

- 1.1.5.1 Malnutrition

- 1.1.5.2 Dehydration

- 1.1.5.3 Quality of life

- 1.1.6. Signs

- To Know More

- Lesson 1.2. Detection, diagnosis and treatment

- 1.2.3 Professionals involved

- 1.2.4. Alert protocol

- 1.2.5. Management of oropharyngeal dysphagia

- 1.2.6. Medical and surgical treatment

- To Know More

Lesson 1.1 Dysphagia

What will I learn in this lesson?

The aim of this module is to understand the definition of dysphagia.

Learning outcomes

To discuss main characteristics of swallowing (definition of swallowing, swallowing phases).

To understand the definition of dysphagia.

To learn about prevalence and dysphagia classification.

To learn about main health consequences: Security complication (choke, obstruction, respiratory infections: including aspiration pneumonia) .

To emphasize the importance of efficacy complication (risk for malnutrition and dehydration, decrease the quality of life).

To identify the signs of dysphagia.

1.1.1 Swallowing

Swallowing is a complex process. Some 50 pairs of muscles and many nerves work to receive food, drink, medicines or saliva, prepare it and move it from the mouth to the stomach.

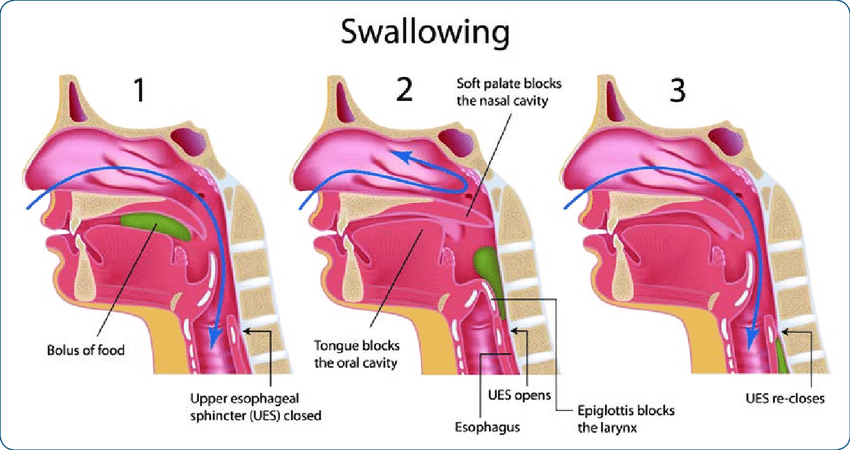

There are three swallowing phases:

-

Oral phase: Voluntary movement of the bolus from the oral cavity into the oropharynx.

-

Pharyngeal phase: Involuntary movement of the bolus from the oropharynx into the esophagus.

-

Esophageal phase: Involuntary movement of the bolus through the esophagus and into the stomach.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

The oral phase of swallowing is the first stage of deglutition and it is a voluntary process. It is also commonly known as the buccal phase. It involves the contraction of the tongue to push the bolus up against the soft palate and then posteriorly into the oropharynx by both the tongue and the soft palate.

Unlike the oral phase, the pharyngeal phase is an involuntary process. First, the tongue is blocking the oral cavity. Then, the nasopharynx is sealed off from the oropharynx and laryngopharynx by elevation of the soft palate and its uvula. The pharynx will then receive the bolus after shortening and widening, at the same time, the larynx will elevate. Finally, the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes and opens, allowing food to enter the esophagus. During this phase, respiration is inhibited, and the epiglottis blocks off the upper airway to prevent the food bolus and liquids from entering the airway and being inhaled. If food does enter the airway, the coughing reflex is triggered. This can happen if someone talks or inhales while swallowing.

The final stage of deglutition is the esophageal phase, which is involuntary. The food bolus is forced inferiorly from the pharynx into the esophagus. Muscle contraction creates a peristaltic ridge. Once the food bolus has fully entered the esophagus, the upper esophageal sphincter will contract and close again. The food bolus then moves through the esophagus via peristalsis, the sequential contractions of adjacent smooth muscle to propel food in one direction. Gravity also aids in the movement of food to the stomach.

1.1.2 Dysphagia

Dysphagia is a swallowing disorder that causes difficulty or sensation of having difficulty swallowing certain foods, liquids, medicines or saliva.

It may involve the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus or gastroesophageal junction and it can range from difficulty with deglutition (the coordinated, active process of passing food and liquids from the oral cavity into the oropharynx and below) to the passive passage of contents from the oropharynx through the esophagus and into the stomach.

Another's swallowing complications.

-

Odynophagia, which is often confused with dysphagia, is defined as pain during swallowing. Both of these symptoms indicate an abnormality—either benign or malignant—that should be further worked up and evaluated.

-

Presbyphagia is the medical term for the characteristic changes in the swallowing mechanism of otherwise healthy older adults. Although age-related changes place older adults at risk of swallowing problems, an older adult’s swallow is not necessarily an impaired swallow, but there are definite changes that can make swallowing more challenging.

Some changes that impact swallowing with ageing may be obvious; for example, missing teeth or dentures may make it more difficult to chew. Other changes are not as easy to see such as changes in the muscles and tissues. In fact, the muscle fibers decrease in size and strength, referred to as sarcopenia, leading to the slowing of pressure generated during swallowing. The elderly often learn to successfully adapt to these physiological changes in early stages. However, with progressing age, swallowing function may deteriorate beyond the patients’ compensatory capacity, eventually presenting as dysphagia.

Dysphagia classification:

-

Oropharyngeal dysphagia. Difficulty or discomfort arising during the swallowing process, from the time the food or drink reaches the mouth and the food bolus is formed, until the upper esophageal sphincter of the esophagus opens. It includes disorders of oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal and upper esophageal sphincter origin and accounts for almost 80% of diagnosed dysphagia. Symptoms usually appear in the first moments after initiating swallowing, although they can also occur during, after or a few minutes after swallowing. Sometimes they can go unnoticed, giving rise to silent aspirations.

-

Esophageal dysphagia. Difficulty or discomfort arising during the swallowing process, from the time the food or drink bolus passes through the upper esophageal sphincter until it reaches the stomach. The main esophageal alterations arise from mechanical obstructive lesions, motor disorders of the upper esophagus, the esophageal body, the lower sphincter or the cardia. Symptoms usually appear several seconds after swallowing and are characteristically referred to the retrosternal and even cervical region. It accounts for 20% of diagnosed dysphagia.

Other classifications can also be made according to:

-

Cause: organic or functional.

-

Establishment: acute or progressive.

-

Duration: transient or permanent.

-

Texture affected: dysphagia to solids, dysphagia to liquids or dysphagia to mixed textures.

Videos:

Normal swallowing and dysphagia:

Explanation of dysphagia:

INDEED project:

1.1.3. Prevalence

Overview

-

Occasional difficulty swallowing, which may occur when you eat too fast or don't chew your food well enough, usually isn't cause for concern. But persistent dysphagia may indicate a serious medical condition requiring treatment.

-

Dysphagia can occur at any age or it may also be associated with pain, disability, chronic diseases and other medical situations. The causes of swallowing problems vary and treatment depends on the cause.

-

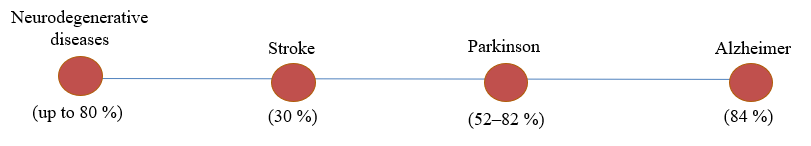

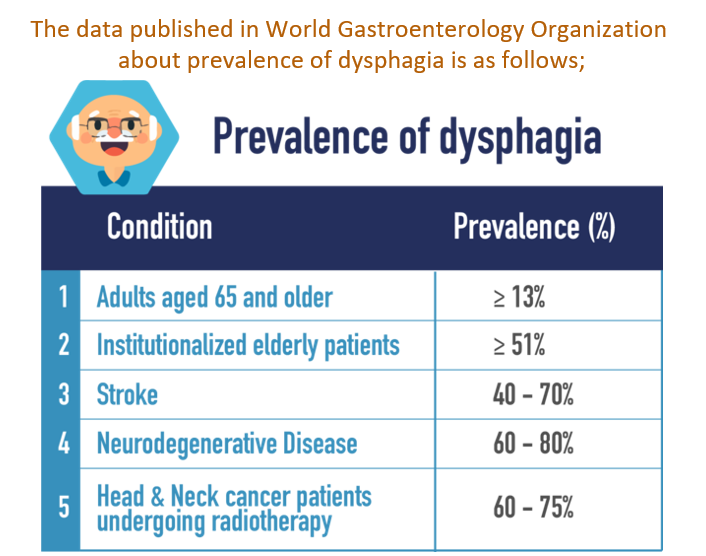

The prevalence of dysphagia is about 8% among the world's adult population. This prevalence is even higher in certain cases; 20-60% in people over the age of 55 and between 35-84% in neurological disease (CP, Alzheimer, ELA …) and other medical situations (surgery, cancer and so on).

Dysphagia is a prevalent difficulty among aging adults. Though increasing age facilitates subtle physiologic changes in swallow function, age-related diseases are significant factors in the presence and severity of dysphagia. Among elderly diseases and health complications, stroke and dementia reflect high rates of dysphagia.

In both conditions, dysphagia is associated with nutritional deficits and increased risk of pneumonia. Recent efforts have suggested that elderly community dwellers are also at risk for dysphagia and associated deficits in nutritional status and increased pneumonia risk.

Dysphagia is projected to become more common in the near future, it is critical to acknowledge it as a national health concern.

The prevalence of dysphagia is about 8% among the world's adult population. This prevalence is even higher in certain cases; 20-60% in people over the age of 55 and between 35-84% in neurological disease (CP, Alzheimer, ELA …) and other medical situations (surgery, cancer and so on)

Disease

prevalence rises with age, and dysphagia is a typical co-occurrence

of many disease processes or therapies.

The prevalence of dysphagia was found to be 11.4 percent in this ‘healthy' older population, which is significant given the demographics.

(Source: obtained from Canva Pro)

-

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a condition that causes difficulty eating and drinking. The personal, social, and economic costs of the situation are not reflected in this sympathetic statement.

-

Dysphagia is a hidden disorder because it can't be seen like hemiplegia or a broken leg. It is frequently a concomitant condition with various neurodegenerative conditions, most notably stroke.

-

Dysphagia prevalence has been reported as a function of care setting, disease condition, and country of inquiry, making it difficult to identify the true prevalence.

Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia has been well-documented as a result of neurologic disorders. Dysphagia in the ‘healthy' population, on the other hand, few research have evaluated the prevalence of dysphagia in European populations.

(Source: obtained from Canva Pro)

1.1.4. Health consequences - Security Complication: Choke, Obstruction, Respiratory Infections, including Aspiration Pneumonia

Consequences of dysphagia include malnutrition and dehydration, aspiration pneumonia, compromised general health, chronic lung disease, choking and even death.

Adults with dysphagia may also experience disinterest, reduced enjoyment, embarrassment, and/or isolation related to eating or drinking.

Dysphagia may increase caregiver costs and burden and may require significant lifestyle alterations for the patient and the patient’s family. It is necessary an interprofessional team to diagnose and manage oral and pharyngeal dysphagia.

Some people have dysphagia and are unaware of it — in these cases, it may go undiagnosed and not be treated, raising the risk security and efficacy complications.

Complications: difficulty swallowing can lead to:

-

Aspiration Pneumonia:

Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection caused by a substantial amount of debris entering the lungs via the stomach or mouth.

-

Obstruction:

Swallowing can be made difficult by conditions that cause a blockage in the throat or a constriction of the esophagus (the tube that transports food from your mouth to your stomach).

-

Choking:

Choking can happen when food becomes caught in the throat. Death can occur if food fully plugs the airway and no one intervenes with a successful Heimlich maneuver.

1.1.4.1 Respiratory Infections: Including Aspiration Pneumonia

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are infections of parts of the body involved in breathing, such as the sinuses, throat, airways or lungs. Most RTIs get better without treatment, but respiratory infections as pneumonia need obligatory treatment.

Increased risk of aspiration results in a number of serious consequences, including chest infections, aspiration pneumonia and increased incidence of mortality

Pneumonia is a breathing condition in which there is inflammation (swelling) or an infection of the lungs or large airways.

People with dysphagia develop an aspiration pneumonias occurs when food, saliva, liquids, or vomit is breathed into the lungs or airways leading to the lungs, instead of being swallowed into the esophagus and stomach.

All of these things may carry bacteria that affect lungs. The 52% of patients with dysphagia suffer from aspiration.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

What are the symptoms of aspiration pneumonia?

• chest pain

• shortness of breath

• wheezing

• fatigue

• blue discoloration of the skin

• cough, possibly with green sputum, blood, or a foul odor

• difficulty swallowing

• bad breath

• excessive sweating

Anyone exhibiting these symptoms should contact their doctor to get medical attention and a quick diagnosis.

Interesting note*: The airway is a complex system of tubes that transmits inhaled air from your nose and mouth into your lungs.

1.1.4.2 Obstruction

An airway obstruction is a blockage in any part

of the airway due to a food or foreign object. An obstruction may

totally prevent air from getting into lungs that would

be life threatening emergencies that require immediate medical

attention.

How is an airway obstruction treated?

-

An airway obstruction is usually a medical emergency. Call a national emergency phone number if someone near you is experiencing an airway obstruction. There are some things you can do to help while you’re waiting for emergency services to arrive.

1.1.4.3 Choking

It is the sensation that food is stuck in your throat or chest and it partially prevents air from getting into lungs. It persists breath and starts coughing to eliminate this strange particle. Sometimes the coughing produces persistent drooling of saliva, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting or other symptoms.

How is an airway choke treated?

-

It is advisable to encourage the person to cough until the element is expelled. It should avoid drinking liquids, eating food or back blows because the foreign object could fall into the airway.

If the person with dysphagia has lost weight accidentally in the last few weeks or months, see a professional.

Many dysphagia patients are concerned about choking or coughing while drinking liquids.

Dysphagia

is associated with a decrease in water intake, which is exacerbated

by the degradation of thirst in elderly persons.  They are at a high risk of dehydration as a result of this.

They are at a high risk of dehydration as a result of this.

The first approach in preventing dehydration is to keep track of how much modified texture fluids you consume on a daily basis.

Aspiration pneumonia is a leading cause of death in the elderly and feeble, as well as in patients who do not cough after aspiration or whose repeated aspirations or pneumonia go unrecognized.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

1.1.5. Health consequences - Efficacy Complications: Malnutrition, Dehydration, Decrease Quality of Life

Due to a loss of appetite or discomfort when swallowing, people who have trouble swallowing generally lower their dietary quantity and diversity. The lack of attraction of crushed or pureed food is another reason why patients with swallowing issues limit their food intake. Colours that are too similar and flavors that are too unfamiliar may be some of the causes for your disinterest.

It's also worth noting that persons with dysphagia are more likely to have chronic conditions like cancer, Alzheimer's disease, stroke, or Parkinson's disease, all of which raise nutritional requirements.

All of these reasons could explain why patients with dysphagia are more likely to lose weight and become malnourished. Malnutrition can be as high as 40% in nursing homes for elderly individuals with dysphagia, according to research published in medical publications.

Complications of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Oropharyngeal dysphagia can range in severity from little difficulties to full inability to swallow. In older people, oropharyngeal dysphagia can cause two types of clinically significant complications: malnutrition and/or dehydration due to a decrease in deglutition efficacy, which can occur in up to 25%–75% of patients with dysphagia; and choking and tracheobronchial aspiration due to the obstruction of the airway.

Complications.

Difficulty swallowing can lead to:

Malnutrition. Malnutrition can result from a reduction in oral eating due to swallowing difficulties.

Dehydration. Dehydration occurs when the body loses more water than it takes in, primarily from the intracellular volume (ICV).Quality of Life. Dysphagia can lead to serious complications like pneumonia, dehydration, starvation, and even death. It has a negative impact on the patients' quality of life and mental health.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

1.1.5.1 Malnutrition

Malnutrition has been defined as a clinical condition of an imbalance of energy, protein, and other nutrients (a lack of important vitamins and minerals) that causes measurable negative effects on body composition, physical function, and clinical outcomes.

51% of people with dysphagia are at risk of malnutrition and severity of dysphagia correlates with increased incidence of malnutrition.

Treatments in malnourished residents suffering from dysphagia are of compensative or rehabilitative nature and include e.g:

Diet modifications.

Nutritional supplementation.

Oral-motor therapy.

Postural techniques.

Facilitation techniques.

Others.

In general, a multidisciplinary approach from an otolaryngologist and/or neurologist and/or gastroenterologist, a clinical geriatrician/ elderly care physician, a radiologist, a speech/ language therapist, a dietician, and a nurse and caregiver, is recommended for safe and efficient swallowing management

1.1.5.2 Dehydration

Dehydration occurs when you use or lose more fluid than you take in, and your body doesn't have enough water and other fluids to carry out its normal functions.

Because fluid intake is restricted in most patients with dysphagia, these individuals are at risk of dehydration. It leads to increased medical costs, morbidity, and mortality. Therefore, the patient's hydration status must be closely monitored and rapidly corrected.

Dehydration may lead to lethargy, mental confusion, and increased aspiration. In addition, dehydration depresses the immune system, making the patient susceptible to infection, and it may also be a risk factor for pneumonia, because it decreases salivary flow (thus promoting altered microbial colonization of the oropharynx).

Other symptoms of dehydration include:

Feeling very thirsty

Dry mouth

Urinating and sweating less than usual

Dark-colored urine

Dry skin

Feeling tired

Dizziness

Confusion

Fainting

Rapid heartbeat

Rapid breathing

Shock.

1.1.5.3 Quality of life

Quality of life may be defined as the degree to which an individual is healthy, comfortable, and able to participate in or enjoy life events.

Previous main complications associated with dysphagia may lead to decreased quality of life and social isolation, besides that place people at high risk for co-morbidities and mortality.

When dysphagia is underestimated, unrecognized (so-called silent dysphagia) or left untreated, they may lead to previous risk as: aspiration pneumonia, dehydration, malnutrition, etc, followed by feelings of social isolation, anxiety or even depression.

All this leads to an increase in dependency, a greater burden of personal and medical care, as well as an increase in institutionalization.

1.1.6. Signs

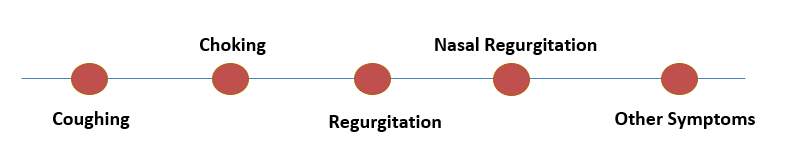

The most common signs of dysphagia are:

Coughing

Coughing is a generic reaction to a wide range of stimuli that usually originates in the pharynx, larynx, or lungs. Coughing that happens during or shortly after swallowing is a clear indicator of a swallowing difficulty.

Patients may not perceive the timing association between coughing and swallowing since humans swallow throughout the day. Coughing may be caused by early leaking of oral contents into the pharynx, insufficient clearing of the bolus from the pharynx, or regurgitation of esophageal contents back to the pharynx, all of which obfuscate this link (Figure 3). Rather than coughing, the phrase "choking" is frequently used to refer to a sensation of food clinging to the throat.

Choking

Patients (and clinicians) frequently use the term "choking" to describe the sensation of food stuck in the esophagus or coughing. Both symptoms are common in people with swallowing difficulties, but they indicate different sources of malfunction. As a result, it's critical to pinpoint exactly what's causing the symptoms when examining them.

Regurgitation

The swallowing process is designed to ensure that the swallowed bolus moves in a single direction. The term "regurgitation" refers to the return of food or fluids to the mouth or pharynx after it has appeared to have passed through.

Regurgitation is the effortless return of material to the mouth or throat. This is in contrast to vomiting, which is characterized by nausea and retching, as well as the contraction of the abdominal muscles and diaphragm.

A swallowing issue is frequently seen when patients say the regurgitated material tastes like eaten food.

Nasal Regurgitation

The nasopharynx shuts by elevating the soft palate and contracting the upper pharyngeal constrictor muscles (superior pharyngeal constrictors). Nasal regurgitation can be caused by a failure of this closure mechanism, pharyngeal retention, or esophagogastric regurgitation.

Other Symptoms

Patients may experience a scratchy throat, hoarseness, shortness of breath, and chest discomfort or pain, depending on the type of swallowing dysfunction. It's possible that the link between swallowing and these symptoms isn't clear. None of these symptoms are particular to swallowing difficulties and could develop from a variety of other causes.

All signs

Signs and symptoms associated with dysphagia may include:

Difficulty picking up food from the cutlery

Storage food in the mouth

Increased time chewing and oral handle

Inability to keep the bolus in the oral cavity

Difficulty performing and coordinating oral movements with the facial, oral and lingual muscles

Loss of strength during chewing.

Excessive chewing pattern.

Lack or decrease in the perception of the food in the mouth.

Difficulty gathering the bolus at the back of the tongue

Hesitation or inability to initiate swallow

Frequent repetitive swallows

Drooling

Rejection of food or beverages that they previously consumed

Delayed or absent laryngeal elevation

Food residue in the mouth after swallowing

Frequent throat clearing Swallow-related cough or gagging: before, during, and after swallowing

Feeling of residue or compaction in the mouth or pharynx

Pain, discomfort or a feeling of stuck in the throat

Sweating, watery eyes and discomfort

Nasal or oral regurgitation

Changes in tone of voice, hoarseness or "wet voice" or nasal

Frequent choking

Airway obstructions

Feeling of choking when swallowing

Changes in breathing during eating

Signs of esophageal dysphagia:

Nausea or vomiting

Nasal, oral or tracheotomy regurgitation

Reflux

Sensation of food getting stuck in the throat or chest, or behind the breastbone.

Retrosternum pain related to swallowing.

Other frequently signs:

Recurrent respiratory infections

Cough during meals or up to 20 minutes later

Recurrent fever or low-grade fever

Color change in the fingers or lips

Low oxygen saturation in the blood

Weight loss

Dehydration

Others.

To Know More

Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby G, Crary MA. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:287-98. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S23404.

Speyer R., Baijens L., Heijnen M., Zwijnenberg I. Effects of therapy in oropharyngeal dysphagia by speech and language therapists: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2010;25(1):40–65. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9239-7

Huppertz VAL, Halfens RJG, van Helvoort A, de Groot LCPGM, Baijens LWJ, Schols JMGA. Association between Oropharyngeal Dysphagia and Malnutrition in Dutch Nursing Home Residents: Results of the National Prevalence Measurement of Quality of Care. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(10):1246-1252. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1103-8.

https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/stages-of-swallowing

https://www.melbswallow.com.au/resources/presbyphagia-or-swallowing-and-ageing/

http://www.ebrsr.com/evidence-review/15-dysphagia-and-aspiration-following-stroke

Lesson 1.2. Detection, diagnosis and treatment

What will I learn in this lesson?

The aim of this module is to learn early identification of disease, use the screening tools, understand the meaning of professionals involved, learn alert protocol and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia, and improve knowledge about medical and surgical treatment possibilities.

Learning outcomes

To understand the extreme importance of detecting and diagnosing signs of dysphagia

To recognize the different diagnostic tests and treatments.

To apply the knowledge for maintain alert every day.

1.2.1. Early identification of signs

Signs detection is an essential part of the treatment of dysphagia people. When dysphagia is underestimated, unrecognized (so-called silent dysphagia) or left untreated, they may lead to previous risks mentioned. For this reason, training elderly or most vulnerable people in dysphagia and other swallowing complications is essential to carry out a correct treatment.

Training to detect dysphagia signs, you should follow next steps:

Keep a close eye on: Control your state of health: weight variations, fatigue, food rejection, swallowing difficulty and other problems. They may indicate a health problem.

Get informed: request information from the health professionals of your health center or disability association.

Detect: Identify the usual signs of dysphagia and how often they appear.

Act: Inform the reference health professional. Follow the specialist's instructions regarding posture, diet and other relevant habits.

The evaluation of dysphagia requires the collection of detailed information by doctors and speech therapists. This information should be provided by the patient or their family/caregiver. Evaluation makes it possible to define the cause of dysphagia in 80-85% of the cases.

The main objective of the diagnostic program is to evaluate two characteristics:

Safety

It refers to the ability to transfer the bolus from the mouth to the stomach without penetration or aspiration into the lower airways.

Efficacy

It refers to the ability to transfer the bolus from the mouth to the stomach without post-swallow pharyngeal residue.

1.2.2. Dysphagia screening tools

1.2.2.1 Medical history

Elaborating a meticulous clinical history allows us to determine, in

80% of cases, the location of the problem, differentiating whether it

is an oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia, it causes and establish

correct diagnosis. The performance of a differential diagnosis makes

it possible to differentiate dysphagia from other clinical pictures

such as Presbyphagia or Odynophagia.

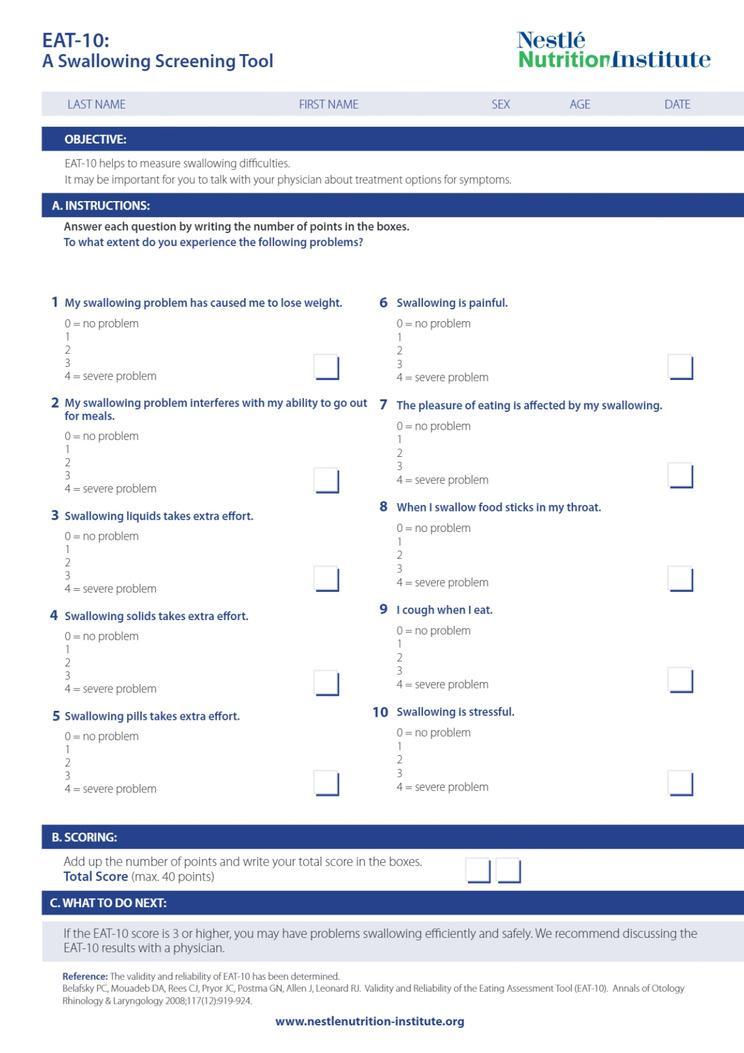

Questionnaires such as EAT-10 (Eating Assessment Tool) are screening tests to identify those individuals at increased risk for clinical signs of dysphagia. They should be thoroughly evaluated and results should be included in medical history.

EAT-10 (Eating Assessment Tool) is a simple and internationally validated questionnaire. It consists of 10 questions to be answered on a scale of values from 0 (no problem) to 4 (serious problem). This tool can be completed by the patient and/or caregiver and is quick to complete (3-5 minutes). If the score is higher than 3, it indicates that the person may have oropharyngeal dysfunction. It is not a valid instrument for the diagnosis of dysphagia.

(Source: obtained from Canva Pro)

1.2.2.2 Clinical examination

Clinical examination is a set of procedures performed by a trained speech-language pathologist, whose purpose is to obtain further clinical information that confirms the diagnostic orientation provided by the medical history.

Clinical information: data of any form, type or kind that allows acquiring or extending knowledge about the physical and health condition of a person to preserve, care for, improve or recover it.

The main objective of clinical examination in dysphagia is to provide the clinician information on the existing deficits, neuromuscular processes involved in swallowing and their modifications. In this way, hypotheses about the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for the disorder can be put forward and select the optimal diagnostic and treatment techniques.

Main clinical explorations:

-

Face, trunk and cervical observation. Paying attention to facial gestures, neck, posture and head position.

-

Oral cavity exploration. Observation of the oral anatomy and physiology: ability to open the mouth, labial, lingual movements in all axes of space, mandibular and cheek movements active and against resistance. Presence or accumulation of residues or saliva, alteration of the chewing capacity, state of teeth and any alteration of the anatomy or physiology of the same.

-

Pharyngolaryngeal motor and sensory examination. Assessment of laryngeal mobility, presence of secretions, glottic function and voluntary cough. The latter is a sign of laryngeal protection against aspiration. People with cervical tracheostomy scar will be explored to ensure that there are no adhesions that limit the mobility of the larynx.

-

Cognitive status assessment. Evaluation of limb mobility, posture, tone, coordination, osteotendinous reflexes and superficial and deep sensitivity. The detection of abnormal movements, dystonia or archaic reflexes (sucking and biting) allows planning the most appropriate guidelines for treatment based on their active collaboration and understanding.

-

Neurological examination of the cranial nerves. Nerves containing motor and sensory fibers. They control the symmetry of the lips, face, protrusion, mobility and strength of the tongue, symmetry of the uvula and palate, oral and oropharyngeal sensitivity, the ability to manage secretions and the ability to cough voluntarily. The assessment of these movements will be done by verbal request, repetition or performance of buccolinguofacial praxias.

-

Exploration of gag reflex, swallowing and cough reflex. Provocation of gagging, swallowing and coughing to assess responsiveness to a complication during feeding, ensuring the safety and efficacy of the process.

-

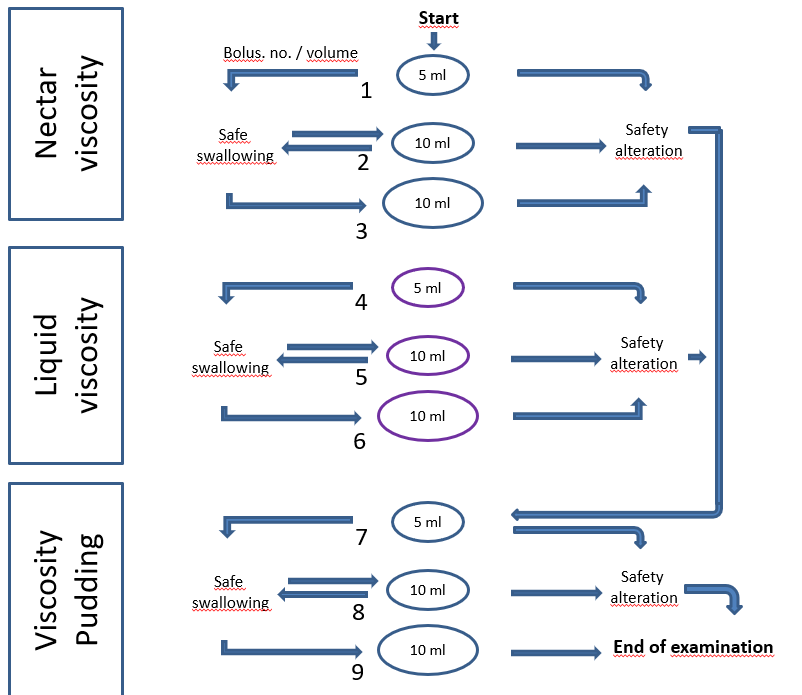

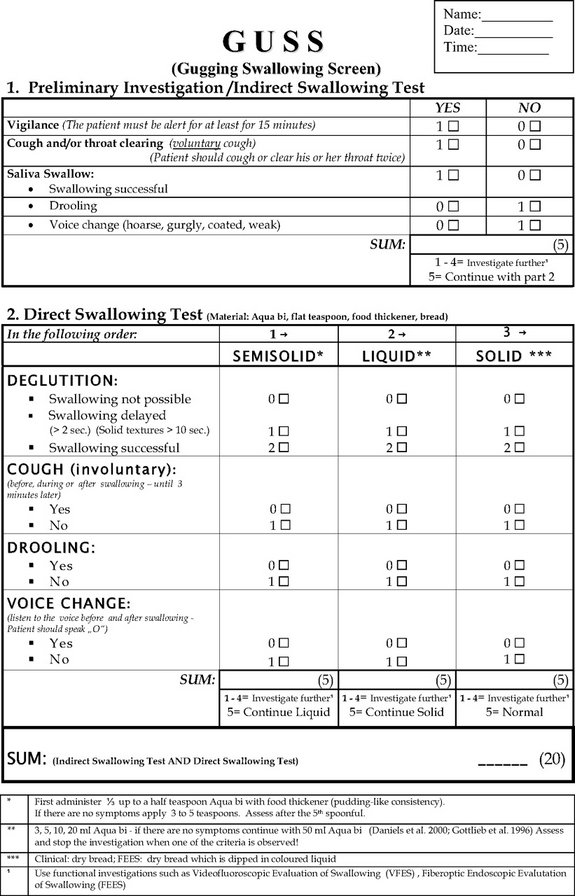

Exploration of swallowing by phases. It aims to locate alterations in the movements and sensitivities of the structures involved in each phase of the swallowing process (oral preparatory phase, oral propulsive phase and pharyngeal phase). Different methods have been developed based on the administration of boluses of different viscosity and volume. These tests can only be recommended and performed by qualified and experienced healthcare personnel, mainly doctors, speech therapists and nurses. The most famous and widely used is the MECV-V because it is a safe and validated method, although there exists others.

MECV-V (clinical examination method volume-viscosity)

GUSS (Gugging Swallowing

Screen)

1.2.2.3 Instrumental assessment

The instrumental assessment looks at functional and structural aspects of swallowing that aren’t visible upon physical examination. It can answer specific questions about the presence and extent of swallow dysfunction, safety for feeding, and the effectiveness of therapeutic strategies.

Health care professionals in most hospitals understand the need for instrumental swallowing assessments. For physicians concerned about further testing, I discuss all the benefits of the information they provide, such as identifying the “why” behind the feeding and swallowing problem and determining effective strategies for safe feeding.

-

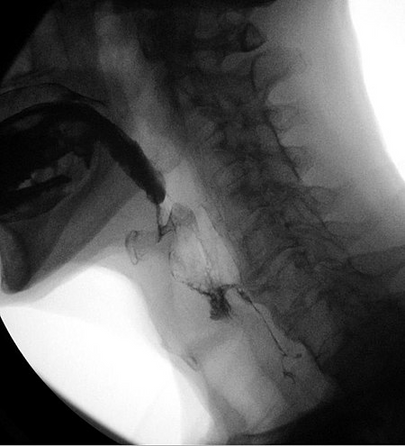

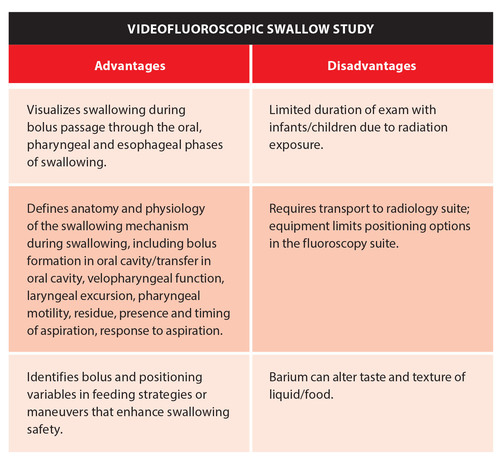

Videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS).

A videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS), also known as a modified barium swallow, is a dynamic x-ray examination of the oral cavity, pharynx and cervical esophagus. VFSS permits evaluation of the patient’s swallowing function through the administration of liquids and solids of varying consistencies to assess swallowing fluoroscopically.

-

Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES).

FEES uses a transnasal endoscope to view the upper aerodigestive tract during swallowing, providing information specific to the pharyngeal phase of swallowing.

-

Cervical auscultation (CA).

It is the use of a listening device, typically a stethoscope in clinical practice, to assess swallow sounds and by some definitions airway sounds. Judgments are then made on the normality or degree of impairment of the sounds.

-

24-hour pH impedance testing.

It is one method your doctor can use to evaluate acid and nonacid reflux from your stomach into your esophagus (the passageway between your mouth and stomach) over the course of a day.

A thin, noodle-like, flexible catheter (tube) inserted into your nose, and guided into the opening of your stomach. The catheter can pick up changes in acidity along its entire length. The catheter conveys information about your acid reflux activity to a computer about the size of a smartphone that you wear on a belt.

Importance of correct treatment in dysphagia

Study of swallowing should be performed by specialized and trained health professionals using specific tools. It allows not only the diagnosis of dysphagia, but also to determine the most appropriate treatment to promote correct oral feeding, reduce the presence of nutritional and respiratory complications as well as the risk of morbidity and mortality, improving the quality of life.

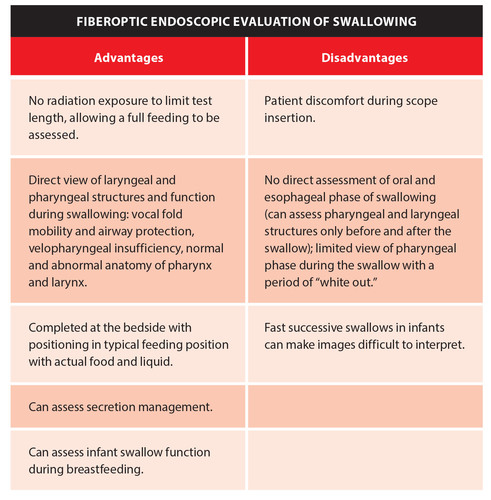

1.2.3 Professionals involved

Dysphagia Team

Individuals with dysphagia (feeding and swallowing disorders) may have a range of medical issues that require evaluation and treatment in a variety of settings (e.g., school, home, hospital, skilled nursing facility).

Dysphagia's causes and consequences cut across traditional professional boundaries and may necessitate the collaboration of many medical or therapeutic specialists. Feeding and swallowing involve the mouth, throat, upper airway, larynx, trachea, esophagus, and stomach.

A multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary team of specialists is best suited to manage people with complicated challenges. To obtain the greatest outcome, these specialists collaborate with one another as well as the patient/student and family.

The Coordinator

A coordinator, who is typically a Speech-Language Pathologist, leads the dysphagia team.

Identifies core team members and support services; facilitates team communication; maintains team focus, communication, and engagement;

Documents team activities; and using appropriate consultation procedures with other team members and other services

Dysphagia team

Dentist /Dental Hygienist: Evaluates and treats gingival and dental dysfunction and may specialize in prosthetics to improve swallowing. Advice on oral hygiene.

Neonatologist: Identifies infants with swallowing difficulties, refers them for evaluation, orders appropriate therapies, and monitors their progress.

Gastroenterologist: Determines any difficulties with the GI tract; performs diagnostic tests related to the esophageal segment of swallowing; and places feeding tubes if the patient/student needs an alternative to oral feeding.

Neurologist: Diagnoses and treats neurological causes of swallowing problems.

Nursing: Works with the patient/student and caregivers in implementing and maintaining safe swallowing techniques and compensatory or facilitation strategies during meals and when taking medications.

Nutritionist/Dietician: Evaluates nutritional needs; follows therapy recommendations regarding consistencies of liquids and solid foods, determines needs for special diets; and ensures adequate nutrition when using alternative means of nutrition.

Occupational therapist: Evaluates and treats sensory and motor impairments and assesses prosthetic needs related to self-feeding and swallowing.

Otolaryngologist: Diagnoses and treats oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal and tracheal pathologies that may cause or contribute to swallowing problems; cooperates with speech-language pathologists in performing endoscopic evaluations of swallowing.

Pediatrician: Identifies children with swallowing challenges, provides appropriate referrals, and integrates the dysphagia team's recommendations with the child's general health and well-being.

Psychologist/ Psychiatrist: Evaluates and treats patient/students and their families in adjusting to dysphagia disability, in coping with ramifications of swallowing disorders, and in managing associated stresses.

Physical Therapist: Evaluates and treats body positioning, sensory and motor movements necessary for safe and efficient swallowing, recommends appropriate seating equipment needed during feeding.

Social Worker: Assists and counsels patient/student and families in adjustment to disability, access to the least restrictive residential and treatment environments, and third-party payment issues.

Pulmonologist: Evaluates and resolves respiratory issues in dysphagia patients/students; controls chronic pulmonary diseases and ventilator-dependent patients/students.

Radiation Oncologist: Implements radiation treatment regimens to treat patients/students with dysphagia caused by malignancies of the mouth, throat, and/or esophagus.

Radiologist: Evaluates swallowing problems through radiologic studies, primarily with Speech-Language Pathologists during videofluorographic swallow studies (VFSS.)

Patient / Student: Provides information to other team members about his/her disorder; demonstrates understanding of the causes and treatment of the dysphagia disorder; follows dietary, compensatory and facilitative techniques to restore swallowing function and maintain adequate nutrition and hydration.

Family Member / Caregiver: Provides information to other team members about the patient/student’s signs and symptoms of the disorder; demonstrates understanding and implements the recommended management techniques.

Speech-Language Pathologist: Evaluates and treats patients/students with swallowing problems, including direct modifications of physiologic responses and indirect approaches such as diet modification.

1.2.4. Alert protocol

Why is the alert protocol necessary?

According to studies conducted by the European Group for the Study of Dysphagia:

up to 36% of patients diagnosed with dysphagia report avoiding dining with others, resulting in increased social isolation.

Since their diagnosis, 41% report an increase in anxiety before eating.

55% believe their quality of life has deteriorated.

All of this leads to a rise in dependency, as well as a greater weight of personal and medical care and institutionalization.

When dysphagia is suspected, what should you do and who should you see?

Dysphagia symptoms might emerge immediately after eating or drinking something or in the next 15-30 minutes. One or more of these indicators must be recognized and identified repeatedly in the diagnosis period.

In the event that indications of dysphagia are detected or suspected, the alert protocol will be the following steps:

Inform your primary care physician. This professional is in charge of performing a preliminary assessment of the symptoms and assessing whether or not the patient is at risk of developing this condition. He is also in charge of referring patients to the appropriate specialist within the HEALTH system if he notices any indicators or has a strong suspicion.

The entity's or association's health personnel should be noticed whether it has a health service or not. The center must inform doctors, nurses, and speech therapists, who will carry out the center's action protocol for dysphagia screening, detection, diagnosis and treatment.

It is vitally important to follow the instructions given by health professionals.

These will be in charge of solving all your doubts, questions and providing you with the real and truthful information you need. In case of not being able to answer the questions posed, they are also the best qualified to refer you to another health professional who can. Searching for information on the internet or social networks is discouraged at all times, as it may not be truthful and may even be dangerous to the health of the person. After the diagnosis, periodic evaluations will be carried out to guarantee that feeding is a safe and effective process, since as the pathology that causes dysphagia progresses, so does the symptom.

ALERT PROTOCOLS FOR DYSPHAGIA IN CENTERS

When a professional receives a warning for

suspected dysphagia alarm sign (s), they must follow the steps below:

The professional will be present during the takings (food-drink) for the next three days in the center to determine if the alert specified is present.

Professionals and family members involved in the person's feeding will be notified of the presence of these symptoms by the reference figure. It will also serve as a reminder of the most common warning indicators.

The Professional will make a note in the center's incident book so that the entire team is aware of the situation. Within the next five days, professionals provide confirmation of supervision.

(Source: obtained from Canva Pro)

If no repeat signs or symptoms of dysphagia are discovered in the next 5 days, the feedings will be monitored as usual. Depending on whether or not a specialized professional is present in the center, proceed as follows if one or more indicators of dysphagia are discovered during the surveillance period.

Without specialized professionals to perform texture assessment tests in the center

Referral to a family doctor through the family or the center for professional examination and texture / thickening instructions. Use textures (solids and liquids) with a texture level more adapted than usual until the test is performed.

Analyzing the situation and deciding on the test to perform

Develop rules for texture and thickening

Inform the center's professionals and family about the new dietary guidelines that have been created.

Include it in the incident book so that everyone on the team is aware of it.

Modify the user's clinical / nutritional file as well as the explanatory food documents.

1.2.5. Management of oropharyngeal dysphagia

Management strategy:

-

Dysphagia sufferers should be identified as soon as possible.

-

Diagnosis of any medical or surgical conditions that may benefit from certain treatments.

-

Therapeutic measures are devised to ensure safe and effective deglutition and proper nutrition.

Preterm infants in dysphagia management

Early detection of high-risk preterm infants is critical. The goal of this evidence-based systematic review is to characterize the nature of preterm baby eating and swallowing issues, identify associated risk factors and calculate the incidence of feeding problems.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

Management of dysphagia in elderly patients

Dysphagia management is a collaborative effort. Many professions may be involved in the treatment of a patient's dysphagia symptoms. To enhance deficient swallowing functions in elderly people, more direct and intensive rehabilitation treatments are required.

1.2.6. Medical and surgical treatment

In order to diagnose and treat swallowing difficulties, a complete medical history and a thorough physical examination are required. A physical examination of the neck, mouth, oropharynx, and larynx should be conducted, as well as a neurologic evaluation.

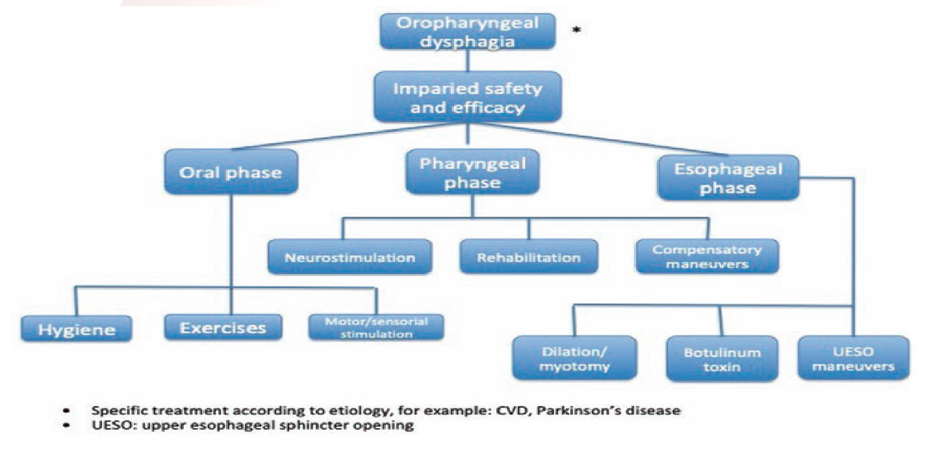

Algorithm for oropharyngeal dysphagia treatment:

Oral phase:

-

Hygiene (For dysphagia patients, oral care entails not just cleaning the mouth, but also avoiding aspiration pneumonia, which can be fatal)

-

Motor/sensorial stimulation; Castillo Morales' orofacial regulation therapy, which combines body and orofacial management with the insertion of a palatal plate, has shown encouraging outcomes in dysphagia patients.

-

Exercises; Dysphagia patients should begin with exercises like the ones described below, under the supervision of a medical expert such as a speech-language pathologist or an occupational therapist.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

(Source: obtained from Canva Pro)

Pharyngeal phase:

-

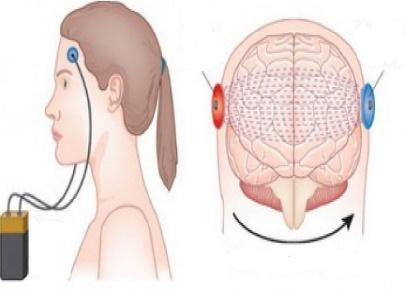

Neurostimulation; Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is a type of transcutaneous stimulation that activates sensory or motor nerve fibers involved in swallowing. This mechanism of action is thought to include increasing central nervous system recuperation and speeding up the development of muscle strength.

(Source: obtained from Canva Pro)

-

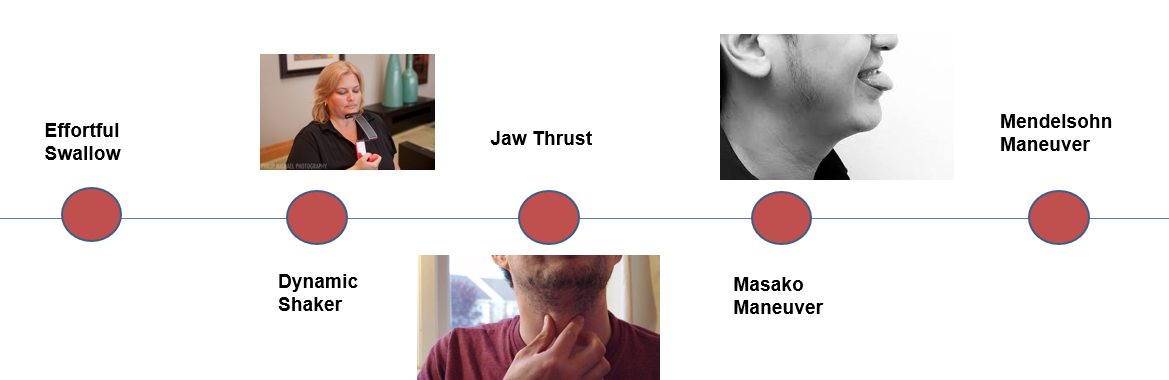

Rehabilitation; Exercises for swallowing rehabilitation are designed to target certain muscles or muscle groups. Much of today's treatment focuses solely on strength, with little evidence-based studies demonstrating the therapeutic benefits of therapeutic exercises.

-

Compensatory maneuvers; When compensatory techniques are adopted, they alter the swallow but do not result in long-term functional changes. A head rotation, which is utilized during the swallow to steer the bolus toward one of the lateral channels of the pharyngeal canal, is an example of a compensating method.

(Source: https://www.istockphoto.com)

Esophageal phase:

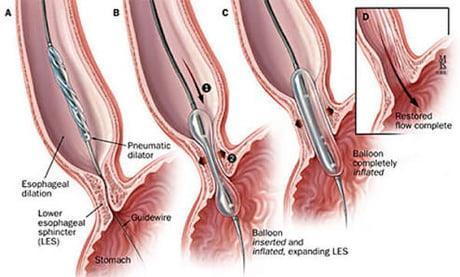

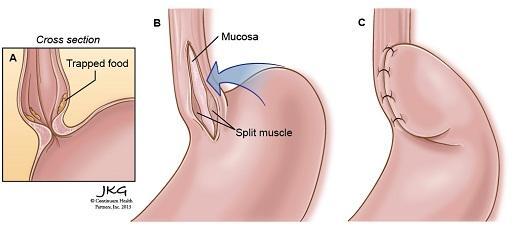

-

Dilation/myotomy; Myotomy can be done through the skin or with an endoscope. Hemorrhage, recurrent laryngeal nerve damage, and pharyngeal or esophageal fistulization are all complications of myotomy.

-

Botolinium toxin; In individuals with OD, BoTox injection might be utilized as the first treatment option. It is simple and safe, and it relieves dysphagia in 43% of instances. Patients with preserved mouth and tongue activity at VFS and intact bolus propulsion capacity on manometry can be offered CP myotomy if BoTox fails.

Surgical treatment of OD. Surgery may be indicated to treat esophageal cancer or to improve swallowing problems caused by throat narrowing or obstructions, such as bony outgrowths, vocal cord paralysis, pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, GERD, and achalasia. Following surgery, speech and swallowing treatment is frequently beneficial.

The type of surgical treatment depends on the cause for dysphagia. Some examples are:

- Laparoscopic Heller myotomy - when the muscle at the lower end of the esophagus (sphincter) fails to open and release food into the stomach in persons with achalasia,

this procedure is used to sever it.

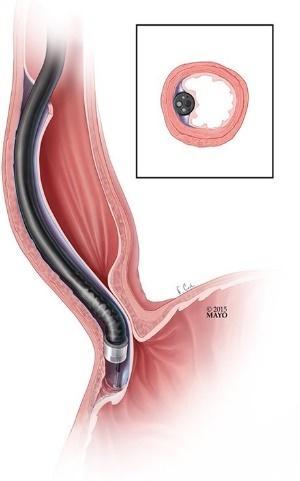

-

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) - an endoscope is put into your mouth and down your throat by the surgeon to make an incision in the lining of your esophagus. The surgeon next cuts the muscle at the lower end of the esophageal sphincter, similar to a Heller myotomy.

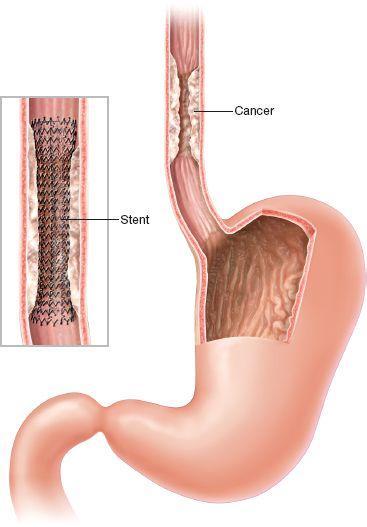

-

Stent placement - a metal or plastic tube (stent) can also be inserted by your doctor to prop open a narrowing or obstruction in your esophagus. Some stents are permanent, such as those for esophageal cancer patients, while others are temporary and removed later.

To Know More

Speyer R., Baijens L., Heijnen M., Zwijnenberg I. Effects of therapy in oropharyngeal dysphagia by speech and language therapists: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2010;25(1):40–65. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9239-7

Pizzorni N, Schindler A, Castellari M, Fantini M, Crosetti E, Succo G. Swallowing Safety and Efficiency after Open Partial Horizontal Laryngectomy: A Videofluoroscopic Study. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(4):549. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040549.

McCullough GH & Martino R. Clinical evaluation of patients with dysphagia: Importance of history taking and physical exam. In: Manual of diagnostic and therapeutic techniques for disorders of deglutition (pp. 11-30). 2013. Springer, New York, NY.

Azpeitia Armán J, Lorente-Ramos RM, Gete García P, Collazo Lorduy T. Videofluoroscopic Evaluation of Normal and Impaired Oropharyngeal Swallowing. Radiographics. 2019;39(1):78-79. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019180070.

Nacci A, Ursino F, La Vela R, Matteucci F, Mallardi V, Fattori B. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES): proposal for informed consent. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28(4):206-11.

Leslie P, Drinnan MJ, Zammit-Maempel I, Coyle JL, Ford GA, Wilson JA. Cervical auscultation synchronized with images from endoscopy swallow evaluations. Dysphagia. 2007 Oct;22(4):290-8. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9084-5.

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/24-hour-ph-impedance-testing

https://www.nestlehealthscience.com/f4d0c0c8-452b-4ee8-bef0-eb8bddd039e8